· Mayank Kashyap · 10 min read

Important Surface Landmarks in the Human Body

Surface anatomy is the cornerstone of clinical examination and medical practice. These external landmarks serve as your roadmap to the hidden structures beneath the skin, enabling you to perform accurate physical examinations,

Important Surface Landmarks in the Human Body

A Comprehensive Guide to Clinical Surface Anatomy

Reading Time: 12 minutes

Last Updated: November 2025

Target Audience: Medical Students, Healthcare Professionals, Anatomy Enthusiasts

Surface anatomy is the cornerstone of clinical examination and medical practice. These external landmarks serve as your roadmap to the hidden structures beneath the skin, enabling you to perform accurate physical examinations, guide surgical procedures, and interpret diagnostic findings. Whether you’re palpating for the sternal angle or locating McBurney’s point, understanding these landmarks transforms abstract anatomy into practical clinical skills.

Table of Contents

1. Understanding Surface Anatomy

2. Thoracic Landmarks

3. Abdominal Landmarks

4. Upper and Lower Limb Landmarks

5. Dermatomes and Neurological Landmarks

6. Clinical Applications

https://res.cloudinary.com/dzqcothug/image/upload/v1763706875/landmark_hlydjm.png Figure 1: Anterior view of the human body highlighting major surface anatomy landmarks and regional terminology

Understanding Surface Anatomy: The Foundation of Clinical Practice

Surface anatomy, also known as superficial anatomy, is the study of external anatomical features and their relationship to deeper internal structures. Unlike the detailed dissections you might see in anatomy labs, surface anatomy focuses on what you can see, feel, and use in everyday clinical practice—making it an indispensable skill for every healthcare professional.

The beauty of surface anatomy lies in its accessibility. You don’t need expensive imaging equipment to identify the jugular notch, feel for the radial pulse, or locate the anatomical snuffbox. These landmarks are always there, patiently waiting beneath your fingertips, ready to reveal the secrets of what lies deeper within the body.

Figure 2: Anatomical position and directional terminology essential for describing surface landmarks

Why Surface Landmarks Matter

In our modern era of CT scans, MRIs, and ultrasounds, you might wonder why we still emphasize physical examination skills. The answer is simple: surface anatomy remains the fastest, most cost-effective, and most accessible diagnostic tool available. When a patient presents with acute abdominal pain, your ability to locate McBurney’s point and elicit rebound tenderness can guide urgent decision-making long before any imaging results arrive.

Clinical Pearl: Surface anatomy bridges the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. A thorough understanding of these landmarks enables rapid assessment during emergencies, precise surgical planning, and accurate interpretation of physical findings.

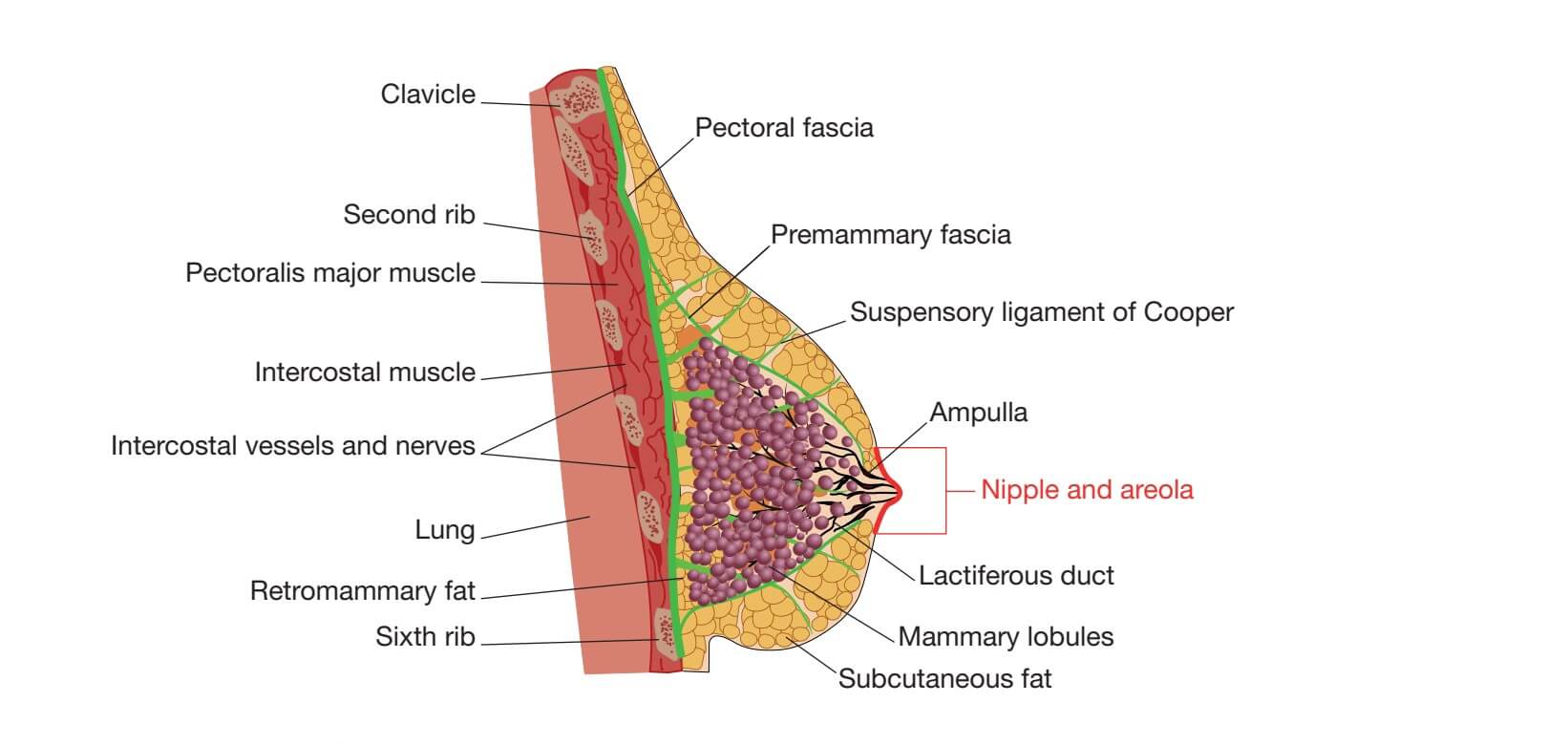

Thoracic Landmarks: Navigating the Chest Wall

The thorax presents some of the most clinically relevant surface landmarks in the entire body. From cardiac auscultation to chest tube insertion, these reference points guide countless procedures every single day in hospitals worldwide.

Figure 3: The sternum with key landmarks including the sternal angle (Angle of Louis), a critical reference point for counting ribs

Sternal Angle (Angle of Louis)

Perhaps the most important landmark on the anterior chest wall, the sternal angle is a slight ridge you can feel where the manubrium joins the body of the sternum. This seemingly simple bump carries enormous clinical significance.

Location: Junction between the manubrium and body of sternum, approximately 5 cm below the jugular notch

Anatomical Level: Corresponds to the T4-T5 intervertebral disc

Rib Identification: The second costal cartilage attaches here, making it your starting point for counting ribs

Clinical Relevance: Marks the level of the tracheal bifurcation, aortic arch, and upper border of the atria

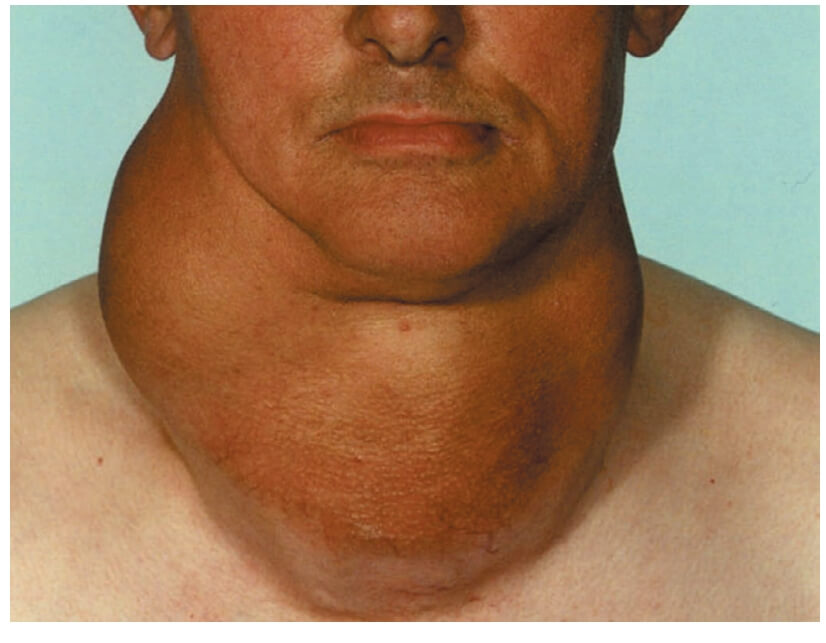

Jugular Notch (Suprasternal Notch)

This U-shaped depression at the superior border of the manubrium is easily palpable and serves as a key reference for central venous access and tracheal assessment.

Anatomical Level: Lies at the level of T2-T3 vertebrae

Clinical Use: Central line insertion, assessment of jugular venous pressure, tracheal deviation

Intercostal Spaces and Rib Counting

The spaces between ribs are numbered according to the rib above them. Accurate rib counting is essential for procedures like thoracentesis and chest tube placement.

2nd Intercostal Space: Aortic area for cardiac auscultation (right sternal border)

3rd Intercostal Space (Erb’s Point): Optimal location for hearing S2 heart sound (left sternal border)

4th Intercostal Space: Location of the nipple in males; left sternal border for tricuspid valve

5th Intercostal Space: Apex beat (midclavicular line), mitral valve auscultation

Thoracic Reference Lines

Vertical reference lines on the chest wall help precisely describe the location of physical findings, guide procedures, and facilitate clear clinical communication.

Midclavicular Line: Vertical line through the midpoint of the clavicle

Anterior Axillary Line: Vertical line along the anterior axillary fold

Midaxillary Line: Vertical line through the apex of the axilla

Posterior Axillary Line: Vertical line along the posterior axillary fold

Scapular Line: Vertical line through the inferior angle of the scapula

Abdominal Landmarks: Mapping the Belly

The abdomen, lacking the rigid skeletal framework of the thorax, relies heavily on surface landmarks for clinical assessment. These reference points help localize pain, guide procedures, and assess organ position.

The Umbilicus

The belly button serves as the most obvious and consistent abdominal landmark, typically located at the level of the L3-L4 intervertebral disc.

Clinical Significance: Divides abdomen into upper and lower halves

Paraumbilical Region: Important for identifying periumbilical pain patterns (early appendicitis, small bowel obstruction)

Portal of Entry: Laparoscopic surgery often uses periumbilical incisions

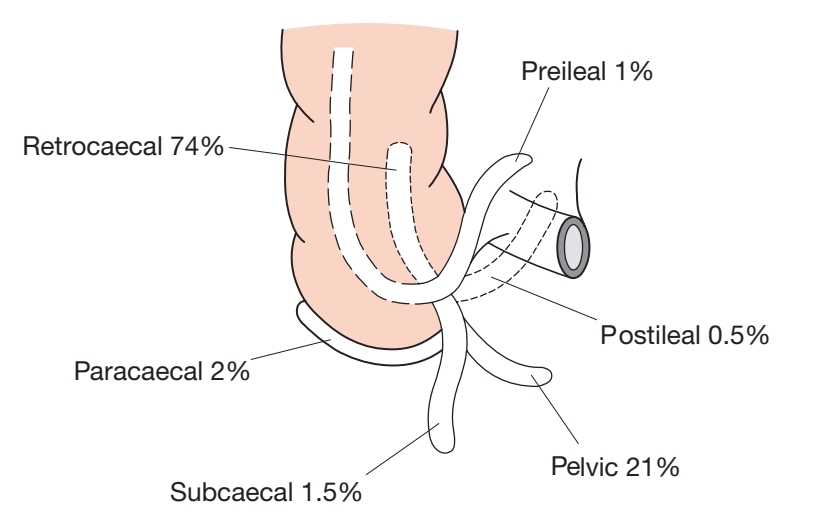

Figure 4: McBurney’s point location—a critical landmark for appendicitis diagnosis

McBurney’s Point

This is arguably the most famous abdominal surface landmark, named after surgeon Charles McBurney who described it in 1889.

Location: One-third of the distance from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the umbilicus

Anatomical Correlation: Overlies the typical location of the appendix base

Clinical Application: Point of maximal tenderness in acute appendicitis

Surgical Relevance: Traditional site for appendectomy incision (McBurney’s incision)

Remember: While McBurney’s point is a valuable landmark, the appendix’s position can vary significantly between individuals. Some appendices point medially, others hang down into the pelvis, and some may even be retrocecal. Always correlate physical findings with the complete clinical picture.

Costal Margin

The inferior edge of the rib cage, formed by the costal cartilages of ribs 7-10, provides important reference points for upper abdominal organs.

Right Costal Margin: Liver palpation, gallbladder (Murphy’s point at the tip of the 9th costal cartilage)

Left Costal Margin: Spleen palpation, stomach fundus

Subcostal Region: Important for subcostal nerve blocks and surgical incisions

Iliac Crest

The superior border of the ilium provides crucial landmarks for procedures and anatomical reference.

Highest Point: Typically at the level of L4 vertebra

Clinical Use: Lumbar puncture site identification (L3-L4 or L4-L5 interspace)

Anatomical Divisions: Helps define boundaries of lumbar and gluteal regions

Abdominal Quadrants and Regions

The abdomen can be divided using surface landmarks into quadrants or nine regions, each system serving different clinical purposes. The four-quadrant system (using umbilicus and median plane) is simpler for quick assessment, while the nine-region system provides more precise localization.

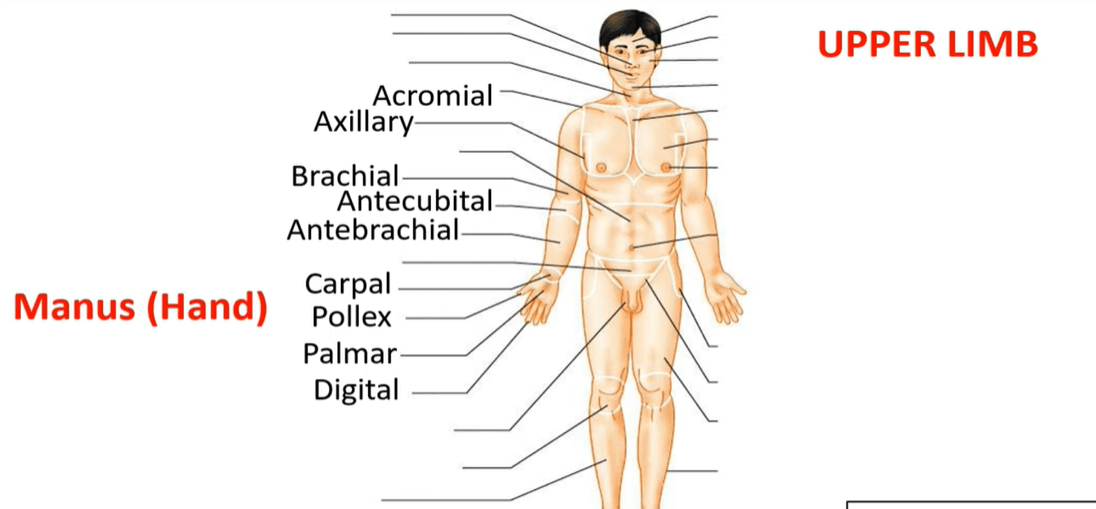

Upper and Lower Limb Landmarks

Upper Limb Landmarks

The upper extremity contains numerous palpable landmarks essential for physical examination, venipuncture, nerve blocks, and orthopedic assessment.

Shoulder Region

Acromion Process: Lateral tip of the scapular spine; reference for deltoid injections

Coracoid Process: Anterior shoulder landmark, palpable just below the clavicle

Greater and Lesser Tubercles: Humeral head landmarks for rotator cuff assessment

Elbow and Forearm

Medial and Lateral Epicondyles: Prominent bony landmarks on either side of the elbow

Olecranon: Tip of the ulna, posterior elbow landmark

Cubital Fossa: Triangular depression anterior to the elbow; common site for venipuncture

Anatomical Snuffbox: Depression at the base of the thumb; tenderness suggests scaphoid fracture

Lower Limb Landmarks

Lower extremity landmarks are crucial for vascular access, joint examination, and regional anesthesia procedures.

Hip and Thigh

Anterior Superior Iliac Spine (ASIS): Prominent anterior projection of iliac crest

Greater Trochanter: Lateral prominence of the proximal femur; landmark for hip injections

Femoral Triangle: Contains femoral artery, vein, and nerve; important for vascular access

Knee and Leg

Patella: Kneecap; reference for knee examination and patellar reflex testing

Tibial Tuberosity: Anterior prominence of the proximal tibia

Medial and Lateral Malleoli: Ankle bone prominences; landmarks for ankle stability assessment

Dermatomes and Neurological Landmarks

Dermatomes represent specific areas of skin innervated by sensory nerves from single spinal nerve roots. Understanding dermatome distribution is essential for neurological examination and lesion localization.

Figure 5: Dermatome map showing cutaneous distribution of spinal nerve roots throughout the body

Key Dermatome Landmarks

Certain dermatome levels correspond to easily identifiable anatomical landmarks, making neurological assessment more systematic and reliable:

C6: Thumb

C7: Middle finger

C8: Little finger

T4: Nipple level

T7: Xiphoid process

T10: Umbilicus

L1: Inguinal ligament

L4: Medial malleolus

L5: Dorsum of the foot

S1: Lateral border of the foot

S2-S4: Perineum (saddle area)

Clinical Application: Testing sensation at these specific landmarks helps identify the level of spinal cord injury or nerve root compression. For example, decreased sensation at the umbilicus suggests a T10 level lesion, while saddle anesthesia (loss of sensation in S2-S4) is a red flag for cauda equina syndrome requiring urgent intervention.

Clinical Applications and Examination Techniques

Physical Examination Mastery

Surface anatomy transforms abstract medical knowledge into practical clinical skills. Every physical examination relies on these landmarks—from the routine vital sign check to complex neurological assessments.

Key Clinical Applications

Cardiac Auscultation: Using intercostal spaces and sternal landmarks to position your stethoscope at the correct valve areas

Respiratory Examination: Counting ribs to identify lung lobes and describe findings precisely

Abdominal Assessment: Systematic palpation using quadrants and specific points like McBurney’s

Venipuncture: Locating the cubital fossa and identifying superficial veins

Regional Anesthesia: Identifying bony landmarks for nerve block placement

Emergency Procedures: Rapid identification of landmarks for chest tube placement, cricothyroidotomy, or emergency vascular access

Palpation Techniques

Successful surface anatomy examination requires proper palpation technique. Use the flat of your fingers rather than fingertips for large structures, and always compare both sides of the body for asymmetry. A gentle, systematic approach yields far better results than forceful prodding, which may cause patient discomfort and muscle guarding.

Practice Tip: Regular practice on yourself and willing friends or family members helps develop the tactile sensitivity needed to identify subtle landmarks. Start with obvious structures like the sternal angle and gradually progress to more challenging landmarks like the coracoid process or scaphoid tubercle.

Modern Applications

While advanced imaging has revolutionized medicine, surface anatomy remains indispensable. Ultrasound-guided procedures still require landmark identification as starting points. Point-of-care ultrasound actually enhances surface anatomy understanding by providing immediate visual feedback about the structures beneath your anatomical landmarks.

Conclusion: The Timeless Value of Surface Anatomy

In an era dominated by technology, surface anatomy stands as a testament to the enduring value of hands-on clinical skills. These landmarks are always available, require no equipment, and provide immediate information that can guide critical decisions. Whether you’re a medical student beginning your clinical rotations or an experienced practitioner refining your examination techniques, mastery of surface anatomy will serve you throughout your entire career.

The human body tells its story through these external landmarks—ridges, depressions, pulsations, and prominences that speak volumes about the structures hidden beneath. Learning to read this anatomical language transforms you from someone who merely looks at patients into a skilled clinician who truly sees them.

Take-Home Points

Surface anatomy bridges theoretical knowledge and practical clinical application

Consistent landmarks like the sternal angle, umbilicus, and ASIS serve as reliable reference points

Dermatome knowledge enables precise neurological localization

Regular practice develops the tactile sensitivity essential for accurate palpation

Surface landmarks remain relevant despite advances in imaging technology

Mastery of surface anatomy enhances diagnostic accuracy and procedural safety

References and Further Reading

Nayak A. Surface Anatomy Foundations Clinical Significance and Modern Applications. Int J Anat Var. 2025; 18(4): 784-784. [https://www.pulsus.com/scholarly-articles/surface-anatomy-foundations-clinical-significance-and-modern-applications.pdf

Rajendran B, et al. Surface Anatomy and Sensory Evaluation of Dermatomes. PMC. 2025 Feb. [https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12097171/

Bandovic I, et al. Anatomy, Bone Markings. StatPearls \[Internet\]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 May. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513259/

Surface Anatomy. Wikipedia. Accessed November 2025. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surface\_anatomy

Anatomical Terminology: Planes, Directions & Regions. Kenhub. Updated September 2023. [https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/anatomical-terminology

](https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/anatomical-terminology)

Surface Anatomy - ScienceDirect Topics. Accessed November 2025. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/surface-anatomy

](https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/surface-anatomy)

Lumley JSP. Surface Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Examination. 5th Edition. CRC Press; 2019.